Social stories are often talked about as a behaviour tool. In reality, they are a regulation and understanding tool.

When written well, a social story helps an autistic or sensory learner make sense of a situation that feels confusing, unpredictable or overwhelming. It gives information, reduces uncertainty and builds emotional safety. It does not correct behaviour. It does not force compliance. It does not tell a child how they should feel.

And that distinction matters.

What is a social story?

A social story is a short, personalised narrative that explains a situation from the learner’s point of view. It describes what is likely to happen, how it might feel, and what support is available.

A good social story answers the questions many autistic learners are constantly holding internally:

- What is happening?

- What will happen next?

- How long will it last?

- Who will be there?

- What will help me feel safe?

It is not a rule list. It is not a warning. It is not a list of expectations disguised as kindness.

Why do social stories work?

Social stories work because they reduce cognitive and emotional load.

Many autistic and sensory learners struggle not because they are unwilling, but because they are uncertain. Uncertainty is exhausting. It increases anxiety, sensory sensitivity and threat responses.

A well written social story:

- Creates predictability

- Reduces anxiety

- Supports emotional regulation

- Prepares the nervous system

- Builds trust

- Supports understanding without pressure

For some learners, this can be the difference between coping and not coping.

What you need to know before you start

The most important part of a social story happens before you write it.

You need to understand:

- The learner’s developmental level, not their age

- How they communicate

- Their sensory profile

- What they already understand about the situation

- What feels hardest or most threatening for them

Then decide the one simple message you want the story to hold.

Not five messages. Not a list of rules. One calm, grounding idea.

For example:

- I am safe.

- I will be supported.

- This will end.

- I can ask for help.

If you do not know that message, the story will drift into adult expectations rather than child understanding.

How to structure a social story

Keep it simple. Always.

Use:

- Literal language

- Short sentences

- One idea per sentence

- Calm, neutral tone

- Honest information

Avoid:

- Idioms or metaphors

- Moral judgement

- Threats or consequences

- Words like must, should or have to

- Over explaining

First person language often works well, but third person can be helpful if the learner finds that easier.

The story should feel like reassurance, not instruction.

The types of sentences that matter

Effective social stories usually include a mix of the following.

Descriptive sentences

These explain what is happening.

“Sometimes school is noisy.”

Perspective sentences

These explain how others might think or feel.

“My teacher wants to help me feel safe.”

Affirmation sentences

These validate the learner.

“It is okay to feel worried.”

Optional coaching sentences

These gently suggest support.

“I can hold my chew if my body needs it.”

Coaching should always be optional and respectful. A social story should never feel demand heavy.

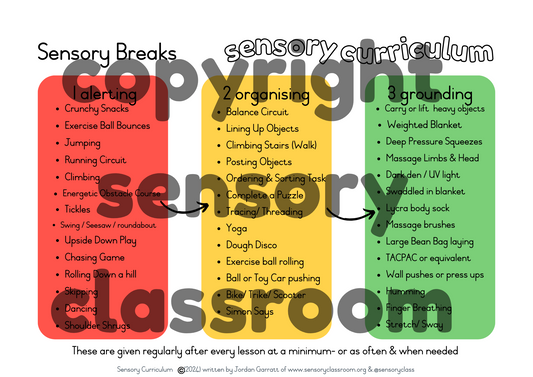

Visuals and sensory considerations

Visuals are not decoration. They are information.

Choose visuals the learner already understands. This might be Widgit symbols, photos, objects of reference or a mix.

Keep layouts calm:

- One image per page

- Plenty of white space

- Neutral backgrounds

- Consistent structure

If sensory input is part of the challenge, include it honestly:

- Sounds

- Lights

- Smells

- Touch

- Movement

Preparation is regulation.

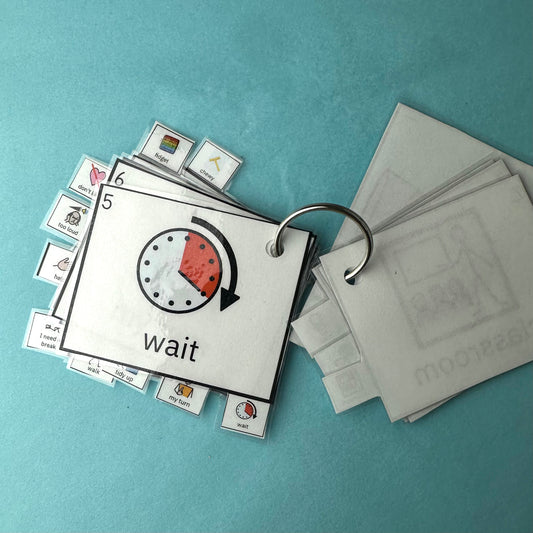

Length and format

Shorter is usually better.

For some learners, four or five sentences is enough. Especially for PMLD learners or children who are already anxious.

Decide:

- Will this be read before, during or after the event?

- Will it be a printed booklet, a laminated card, a digital slide or part of an AAC system?

- Who will read it and how often?

Introduce it calmly, without testing or quizzing. Familiarity builds safety.

Common mistakes to avoid

Many social stories fail because they are written for adults, not learners.

Avoid:

- Turning the story into a behaviour plan

- Using it to control or stop behaviour

- Overloading with expectations

- Writing what you want the child to do rather than what they need to understand

- Making it too long or visually busy

If a story is not helping, simplify it. Remove demands. Reduce language. Return to the core message.

What makes a social story truly effective

A good social story does not change a child. It changes their relationship with a situation.

It tells them:

- You are not wrong for feeling this way

- You are allowed to need support

- You are safe

- You are not alone

That is why social stories, when written thoughtfully, can be so powerful.

They are not about fixing behaviour. They are about building understanding, predictability and trust.

If you get those right, the rest often follows.

You can access my editable Social Story template here: https://sensoryclassroom.org/products/editable-social-story-template

Gray, C. (1994). The original social story book. Jenison Public Schools.

Original introduction of Social Stories, outlining purpose, structure, and intended use.

Gray, C. (2010). The new social story book (10th anniversary ed.). Future Horizons.

Updated guidance on writing and implementing Social Stories, including fidelity criteria and ethical use.

Gray, C. (2015). The new Social Story™ book (15th anniversary ed.). Future Horizons.

Widely cited reference detailing the Social Story™ criteria, sentence types, and rationale.

Gray, C., & Garand, J. D. (1993). Social stories: Improving responses of students with autism with accurate social information. Focus on Autistic Behavior, 8(1), 1–10.

Early empirical paper demonstrating positive effects on understanding and behaviour.

Kokina, A., & Kern, L. (2010). Social Story™ interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(7), 812–826.

Meta-analysis examining effectiveness across multiple studies, highlighting benefits and limitations.

McGill, R. J., Baker, D., & Busse, R. T. (2015). Social Stories™: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3476–3486.

Comprehensive review assessing effect sizes and methodological quality.

Reynhout, G., & Carter, M. (2006). Social Stories™ for children with disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(4), 445–469.

Examines outcomes and cautions around implementation fidelity.

Hutchins, T. L., Prelock, P. A., & Bonazinga, L. (2012). Psychometric evaluation of the Theory of Mind Inventory (ToMI): A tool relevant to social understanding interventions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(3), 327–341.

Often cited to contextualise how Social Stories may support social cognition and perspective-taking.

Barry, L. M., & Burlew, S. B. (2004). Using Social Stories to teach choice and play skills to children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(1), 45–51.

Demonstrates application in structured and play-based contexts.

Sansosti, F. J., Powell-Smith, K. A., & Kincaid, D. (2004). A research synthesis of Social Story interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(4), 194–204.

Early synthesis highlighting strengths, variability, and need for individualisation.

Smith, J. D. (2001). Using Social Stories to enhance behaviour in children with autistic spectrum difficulties. Educational Psychology in Practice, 17(4), 337–345.

UK-based paper supporting use in educational settings.

Ali, S., & Frederickson, N. (2006). Investigating the evidence base of Social Stories™. Educational Psychology in Practice, 22(4), 355–377.

Critical review examining evidence quality and appropriate use.

Crozier, S., & Tincani, M. (2007). Effects of Social Stories on prosocial behavior of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1803–1814.

Supports use with younger children to increase social engagement.

Test, D. W., Richter, S. H., Knight, V. F., & Spooner, F. (2011). A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of Social Stories for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Later review reinforcing cautious but positive conclusions when used appropriately.

Ozsivadjian, A., et al. (2014). Anxiety and repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder: Links to intervention approaches. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Frequently cited to contextualise Social Stories as an anxiety-reducing, predictability-enhancing strategy.

Hume, K., Boyd, B., Hamm, J., & Kucharczyk, S. (2014). Supporting independence in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research and Treatment.

Provides context for using Social Stories with older learners and adults to support independence and transitions.